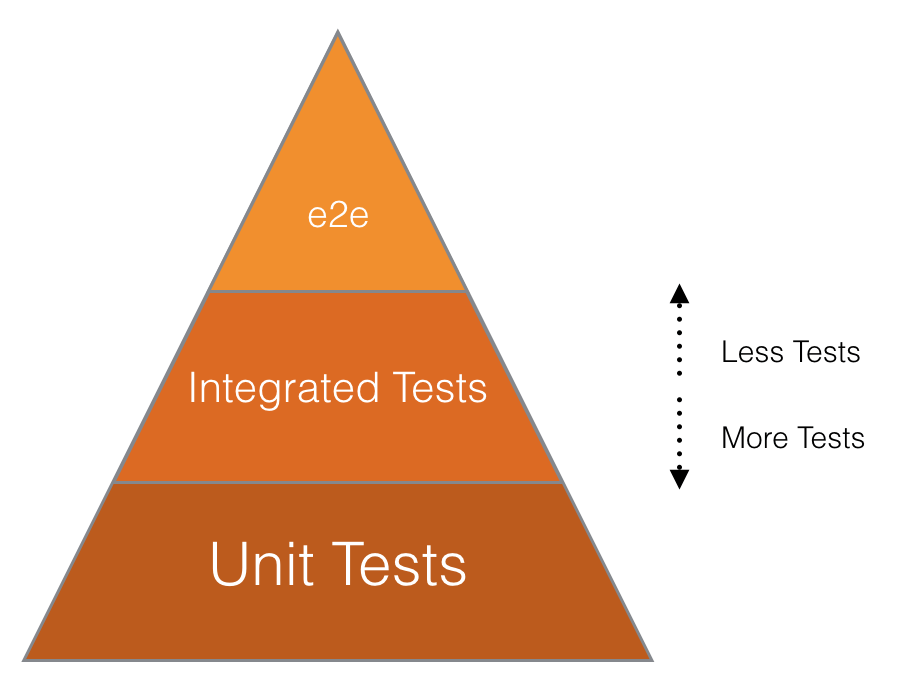

Testing levels

This diagram demonstrates the relative priority of each test type we use. e2e stands for end-to-end.

Unit tests

Formal definition: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unit_testing

These kind of tests ensure that a single unit of code (a method) works as expected (given an input, it has a predictable output). These tests should be isolated as much as possible. For example, model methods that don't do anything with the database shouldn't need a DB record. Classes that don't need database records should use stubs/doubles as much as possible.

| Code path | Tests path | Testing engine | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

app/finders/ |

spec/finders/ |

RSpec | |

app/helpers/ |

spec/helpers/ |

RSpec | |

app/db/{post_,}migrate/ |

spec/migrations/ |

RSpec | More details at spec/migrations/README.md. |

app/policies/ |

spec/policies/ |

RSpec | |

app/presenters/ |

spec/presenters/ |

RSpec | |

app/routing/ |

spec/routing/ |

RSpec | |

app/serializers/ |

spec/serializers/ |

RSpec | |

app/services/ |

spec/services/ |

RSpec | |

app/tasks/ |

spec/tasks/ |

RSpec | |

app/uploaders/ |

spec/uploaders/ |

RSpec | |

app/views/ |

spec/views/ |

RSpec | |

app/workers/ |

spec/workers/ |

RSpec | |

app/assets/javascripts/ |

spec/javascripts/ |

Karma | More details in the Frontend Testing guide section. |

Integration tests

Formal definition: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Integration_testing

These kind of tests ensure that individual parts of the application work well together, without the overhead of the actual app environment (i.e. the browser). These tests should assert at the request/response level: status code, headers, body. They're useful to test permissions, redirections, what view is rendered etc.

| Code path | Tests path | Testing engine | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

app/controllers/ |

spec/controllers/ |

RSpec | |

app/mailers/ |

spec/mailers/ |

RSpec | |

lib/api/ |

spec/requests/api/ |

RSpec | |

lib/ci/api/ |

spec/requests/ci/api/ |

RSpec | |

app/assets/javascripts/ |

spec/javascripts/ |

Karma | More details in the JavaScript section. |

About controller tests

In an ideal world, controllers should be thin. However, when this is not the case, it's acceptable to write a system/feature test without JavaScript instead of a controller test. The reason is that testing a fat controller usually involves a lot of stubbing, things like:

controller.instance_variable_set(:@user, user)and use methods which are deprecated in Rails 5 (#23768).

About Karma

As you may have noticed, Karma is both in the Unit tests and the Integration tests category. That's because Karma is a tool that provides an environment to run JavaScript tests, so you can either run unit tests (e.g. test a single JavaScript method), or integration tests (e.g. test a component that is composed of multiple components).

System tests or feature tests

Formal definition: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/System_testing.

These kind of tests ensure the application works as expected from a user point of view (aka black-box testing). These tests should test a happy path for a given page or set of pages, and a test case should be added for any regression that couldn't have been caught at lower levels with better tests (i.e. if a regression is found, regression tests should be added at the lowest-level possible).

| Tests path | Testing engine | Notes |

|---|---|---|

spec/features/ |

[Capybara] + [RSpec] | If your spec has the :js metadata, the browser driver will be Poltergeist, otherwise it's using RackTest. |

Consider not writing a system test!

If we're confident that the low-level components work well (and we should be if we have enough Unit & Integration tests), we shouldn't need to duplicate their thorough testing at the System test level.

It's very easy to add tests, but a lot harder to remove or improve tests, so one should take care of not introducing too many (slow and duplicated) specs.

The reasons why we should follow these best practices are as follows:

- System tests are slow to run since they spin up the entire application stack in a headless browser, and even slower when they integrate a JS driver

- When system tests run with a JavaScript driver, the tests are run in a different thread than the application. This means it does not share a database connection and your test will have to commit the transactions in order for the running application to see the data (and vice-versa). In that case we need to truncate the database after each spec instead of simply rolling back a transaction (the faster strategy that's in use for other kind of tests). This is slower than transactions, however, so we want to use truncation only when necessary.

Black-box tests or end-to-end tests

GitLab consists of multiple pieces such as GitLab Shell, GitLab Workhorse, Gitaly, GitLab Pages, GitLab Runner, and GitLab Rails. All theses pieces are configured and packaged by GitLab Omnibus.

GitLab QA is a tool that allows to test that all these pieces integrate well together by building a Docker image for a given version of GitLab Rails and running feature tests (i.e. using Capybara) against it.

The actual test scenarios and steps are part of GitLab Rails so that they're always in-sync with the codebase.

Read a separate document about end-to-end tests to learn more.

EE-specific tests

EE-specific tests follows the same organization, but under the ee/spec folder.

How to test at the correct level?

As many things in life, deciding what to test at each level of testing is a trade-off:

- Unit tests are usually cheap, and you should consider them like the basement of your house: you need them to be confident that your code is behaving correctly. However if you run only unit tests without integration / system tests, you might miss the big picture!

- Integration tests are a bit more expensive, but don't abuse them. A system test is often better than an integration test that is stubbing a lot of internals.

- System tests are expensive (compared to unit tests), even more if they require a JavaScript driver. Make sure to follow the guidelines in the Speed section.

Another way to see it is to think about the "cost of tests", this is well explained in this article and the basic idea is that the cost of a test includes:

- The time it takes to write the test

- The time it takes to run the test every time the suite runs

- The time it takes to understand the test

- The time it takes to fix the test if it breaks and the underlying code is OK

- Maybe, the time it takes to change the code to make the code testable.

Frontend-related tests

There are cases where the behaviour you are testing is not worth the time spent running the full application, for example, if you are testing styling, animation, edge cases or small actions that don't involve the backend, you should write an integration test using Jasmine.